What does it take to let ChatGPT manage my Todoist tasks?

I have always been fascinated with the idea of AI-based assistants like Jarvis and Friday. Recently, this fascination was rekindled when I read about the Baby AGI project. This made me want to implement an LLM agent for myself. I also have the ideal use case for it. I’m a big user of Todoist, but like many Todoist users, I’m better at filling my Todoist inbox than cleaning it up. Therefore, I would like an AI assistant to help me with this. For example, it could do the following things for me: group similar tasks, move tasks to the correct project, or even create new projects if no suitable project exists. As you can see in the demo video below, I succeeded.

Now, you might be wondering how I did this. It all comes down to the following questions:

- How do you let LLM preform actions?

- How do you force the agent to adhere to the REACT framework?

- How do you parse and validate the agent’s response?

- How do you handle LLMs that makes mistakes?

In this blog, I will show some code snippets to explain what is happening. However, due to space constraints, I cannot show all the code in this blog. If you want to read the entire codebase, you can find it here.

How do you let LLM preform actions?

Before diving into the implementation details, we must first discuss some background information about how to give LLMs the ability to perform actions. The aim of this project was to have an LLM with whom we could have a conversation, and if, during this conversation, we tell the LLM to perform a particular task, it should be able to do so. For example, if we tell the LLM to clear my inbox, it should tell me it is on it and start performing this task. Once it is done, it should tell me, and we continue our conversation. This sounds simple, but it differs from the typical chat process we are used to. The process now consists of two parts: the conversation part and a new background process part. In this background part, the LLM autonomously selects and performs actions that help it to complete the task we gave it. You can think about this process as something like this:

An example of the workflow of an autonomous agent that performs tasks given to it by the user.

LLMs cannot do this by default since they cannot perform actions independently. They can only respond to us with generated text. However, if you ever let an LLM help you debug a program, you know it can tell you what action you should take. Typically, you perform this action for the LLM; if it does not yet work, you provide it with the resulting error message. You repeat this process until you solve the problem. In this scenario, you act similarly to the background process from the above image. This approach works, but we want something more autonomous. To do this, we need to let the LLM respond in a parsable format that tells us if it wants to perform a particular action. A Python script can then parse this response, perform the action for the LLM, and feed the result back into the LLM. This process allows the LLM to perform actions autonomously. This prompting technique is called REACT and is the basis of this project. The system prompt of this framework looks like this:

Use the following format:

Thought: you should always think about what to do

Action: the action to take, should be one of [{tool_names}]

Observation: the result of the action

... (this Thought/Action/Action Input/Observation can repeat N times)

Thought: I now know the final answer

Final Answer: the final answer to the original input question

So, the LLM’s response now consists of a The same workflow as above but now with the REACT framework.Thought and Action part.

The Thought part is where the LLM can explain its thought process, allowing it to reason about its progress and previous observations.

This part is based on the Chain-of-Thought technique and helps to focus the attention of the LLM.

The Action part lets the LLM tell us what action it wants to perform.

The LLM still cannot perform this action independently, but at least it can now indicate that it wants to perform a particular action.

A Python script can then parse this action and perform it for the LLM.

The output of this action is then fed back into the LLM as the Observation part.

This process can then repeat until the LLM has completed its task.

It will then write the Final Answer part, this part contains the text that will be shown to the user.

For example, “I’m done with X.” and from here the conversation can continue as usual.

That is the basic idea behind the REACT framework.

Now, let’s see how we can implement this.

How do you force the agent to adhere to the REACT framework?

When I started this project, I quickly learned that letting a LLM perform actions is not as easy as it sounds. Implementing the REACT framework is not that hard, but handling all the edge cases is. Most interestingly, all these edge cases arise if you are not explicit enough in your system prompt. It is just like telling a child to clean up its room. If you are not explicit enough, it will most likely misinterpret your instructions or, even worse, find a way to cheat. For example, one of my first prompts looked something like the prompt below. You don’t have to read it all, but it will give you an idea of how long a prompt can become if you have to explain all the rules and edge cases.

def create_system_prompt():

return """

You are a getting things done (GTD) ai assistant.

You run in a loop of Thought, Action, Action Input, Observation.

At the end of the loop you output an Answer to the question the user asked in his message.

Use the following format:

Thought: here you describe your thoughts about process of answering the question.

Action: the action you want to take next, this must be one of the following: get_all_tasks, get_inbox_tasks or get_all_projects, move_task, create_project.

Observation: the result of the action

.. (this Thought/Action/Observation can repeat N times)

Thought: I now know the final answer

Final Answer: the final answer to the original input question

Your available actions are:

- get_all_tasks: Use this when you want to get all the tasks. Return format json list of tasks.

- get_inbox_tasks: Use this get all open tasks in the inbox. Return format json list of tasks.

- get_all_projects: Use this when you want to get all the projects. Return format json list of projects.

- move_task[task_id=X, project_id=Y]: Use this if you want to move task X to project Y. Returns a success or failure message.

- create_project[name=X]: Use this if you want to create a project with name X. Returns a success or failure message.

Tasks have the following attributes:

- id: a unique id for the task. Example: 123456789. This is unique per task.

- description: a string describing the task. Example: 'Do the dishes'. This is unique per task.

- created: a natural language description of when the task was created. Example: '2 days ago'

- project: the name of the project the task is in. Example: 'Do groceries'. All tasks belong to a project.

Projects have the following attributes:

- id: a unique id for the project. Example: 123456789. This is unique per project.

- name: a string describing the project. Example: 'Do groceries'. This is unique per project.

- context: a string describing the context of the project. Example: 'Home'. Contexts are unique and each project belongs to a context.

"""

You might think the prompt is rather explicit and should work. Sadly, the LLM found multiple ways to misinterpret this prompt and make mistakes. Just a small selection of things that went wrong:

- The LLM kept formatting the

move_taskin different ways. For example,move_task[task_id=X, project_id=Y],move_task[task_id = X, project_id = Y],move_task[X, Y],move_task[task=X, project=Y]. This made parsing it rather tricky. - It tried to pick actions that did not exist. For example,

loop through each task in the inbox. - The LLM kept apologizing for making mistakes. Due to these apologies, the format of the response no longer adhered to the REACT framework, resulting in parsing failures (and more complex code to handle these failures).

- and many more…

I tried to fix these issues by making the system prompt more explicit, but that was to no avail.

After some reflection, I realized that code is more expressive than text.

Therefore, I decided to define the response format as JSON schema and asked the LLM only to generate JSON that adheres to this schema.

For example, the schema for the move_task action looks like this:

{

"title": "MoveTaskAction",

"description": "Use this to move a task to a project.",

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"type": {

"title": "Type",

"enum": [

"move_task"

],

"type": "string"

},

"task_id": {

"title": "Task Id",

"description": "The task id obtained from the get_all_tasks or get_all_inbox_tasks action.",

"pattern": "^[0-9]+$",

"type": "string"

},

"project_id": {

"title": "Project Id",

"description": "The project id obtained from the get_all_projects action.",

"pattern": "^[0-9]+$",

"type": "string"

}

},

"required": [

"type",

"task_id",

"project_id"

]

}

This schema is way more explicit than any natural language based explanation I could write.

Even better, I can also add additional validation constraints like regex patterns.

You might think that it might be way more work to create these type of schemas than to write a system prompt.

However, thanks to the Pydantic library, this is not the case.

Pydantic has a schema_json method that automatically generates this schema for you.

So, in practice you will only write the following code:

class MoveTaskAction(pydantic.BaseModel):

"""Use this to move a task to a project."""

type: Literal["move_task"]

task_id: str = pydantic.Field(

description="The task id obtained from the"

+ " get_all_tasks or get_all_inbox_tasks action.",

regex=r"^[0-9]+$",

)

project_id: str = pydantic.Field(

description="The project id obtained from the get_all_projects action.",

regex=r"^[0-9]+$",

)

And the Pydantic model for the expected response from the LLM looks like this:

...

class ReactResponse(pydantic.BaseModel):

"""The expected response from the agent."""

thought: str = pydantic.Field(

description="Here you write your plan to answer the question. You can also write here your interpretation of the observations and progress you have made so far."

)

action: Union[

GetAllTasksAction,

GetAllProjectsAction,

CreateNewProjectAction,

GetAllInboxTasksAction,

MoveTaskAction,

GiveFinalAnswerAction,

] = pydantic.Field(

description="The next action you want to take. Make sure it is consistent with your thoughts."

)

...

# The rest of action models excluded for brevity

Now with these Pydantic models, I tell the LLM to only respond with JSON that adheres to this schema. I do this using the following system prompt:

def create_system_prompt():

return f"""

You are a getting things done (GTD) agent.

You have access to multiple tools.

See the action in the json schema for the available tools.

If you have insufficient information to answer the question, you can use the tools to get more information.

All your answers must be in json format and follow the following schema json schema:

{ReactResponse.schema()}

If your json response asks me to preform an action, I will preform that action.

I will then respond with the result of that action.

Do not write anything else than json!

"""

Thanks to this change in the system prompt, the LLM stopped making the previously mentioned formatting issues. As a result, I needed to cover way fewer edge cases, allowing me to simplify my code base significantly. This makes me, as a developer, always very happy.

How do you parse and validate the agent’s response?

At this point, we have an LLM that always responds with JSON and the LLM knows that this JSON must adhere to the schema from the above Pydantic model.

We still need to parse this JSON and extract the action the LLM wants to perform from it.

This is where Pydantic shines.

Pydantic’s parse_raw function can do all the parsing and validation for us.

If the JSON adheres to the schema, it will return an instance of the model.

These Pydantic models work remarkably well with Python’s match statement, allowing us to select the correct action easily.

Within these cases, we perform the action and API call for the LLM and feed back the result as the observation.

This results in action parsing and selecting code that looks roughly like this:

response = ReactResponse.parse_raw(response_text)

match response.action:

case GetAllTasksAction(type="get_all_tasks"):

... # preform get_all_tasks action

observation = ...

case GetAllProjectsAction(type="get_all_projects"):

... # preform get_all_projects action

observation = ...

case CreateNewProjectAction(type="create_project", name=name):

... # preform create_project action

observation = ...

case GetAllInboxTasksAction(type="get_inbox_tasks"):

... # preform get_inbox_tasks action

observation = ...

case MoveTaskAction(type="move_task", task_id=task_id, project_id=project_id):

... # preform move_task action

observation = ...

case GiveFinalAnswerAction(type="give_final_answer", answer=answer):

... # preform give_final_answer action

return answer

Inside these case statements, we execute the action the LLM wants to perform.

For example, if the LLM wants to move a task, we use the task_id and project_id attributes from the MoveTaskAction object to perform the API call for the LLM.

We create an observation for the LLM based on what happens during this API call.

In the case of the move_task action, this observation is a success or failure message.

In the case of data-gathering actions like get_all_tasks and get_all_projects, the observation is a JSON list that contains the requested data.

We then send this observation to the LLM so that it can start generating its subsequent response, which brings us back to the start of this code.

We keep looping over this code until the LLM performs the give_final_answer action. (Or until another early stopping condition is met, like a maximum number of actions or a time limit.)

We then break the loop and return the message the LLM wants to send to the user, allowing the conversation to continue.

How do you handle LLMs that makes mistakes?

We now have an LLM that can perform actions autonomously and we found a way to prevent it from making formatting mistakes. However, these are not the only mistakes an LLM can make. The LLM can make logical mistakes as well. For example, it might:

- Try to create a project with a name that already exists.

- Try to move a task to a project that does not exist.

- Try to move a task with a

task_idthat does not exist. - Etc.

Handling these mistakes is tricky. We could check for these mistakes, but we likely end up replicating all the (input-validation) logic in the Todoist API. Instead, a more exciting and less complex approach is just trying to perform the action. If an exception occurs, we catch it and feed the exception message back to the LLM as the observation. This approach will automatically inform the LLM that it made a mistake and give all the necessary information to correct it. The code for this approach looks roughly like this:

...

try:

...

match response.action:

...

except Exception as e:

observation = f"""

Your response caused the following error:

{e}

Please try again and avoid this error.

"""

...

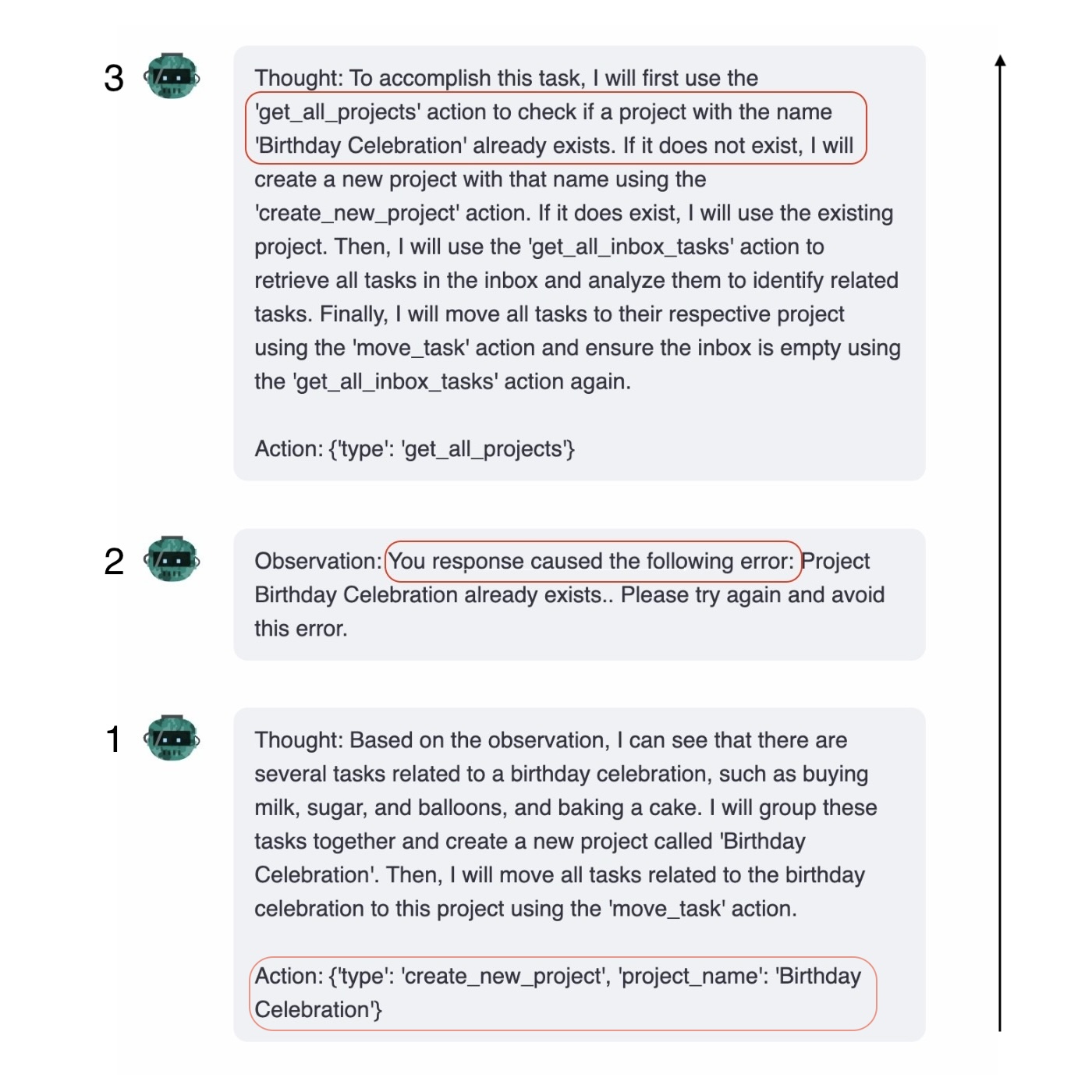

For example, in the image below, you see the LLM is a bit eager and tries to make a new project but there is already a project with that name.

This results in an exception, which is then fed back to the LLM as the observation.

The LLM reasons about this exception and then decided it should try to obtain all the projects first using the get_all_projects action.

An example of an LLM making a mistake and recovering from it based on the exception message.

I find this fascinating. The LLM recognized its mistake and devised a solution to fix it. So, this approach works remarkably well. It works even better if you have exception messages explaining what went wrong and suggesting how to fix it. These things are already best practices for human-intended exception messages. Thus, I find it funny that these best practices also transfer to the LLM-agent domain.

Wrap up

You now have a basic understanding of the REACT framework and how I implemented it in my Todoist agent. This proof of concept project was very insightful for me. What surprised me the most during this project was that the bugs and issues I encountered are remarkably differed from ordinary software development bugs. These bugs felt more like miscommunications between humans than actual software bugs. This observation makes me wonder if there are other inspirations we can get from the communication field and apply them to the LLM agent field. That might be something to explore in a future project. Anyway, I hope this blog inspired you to try the REACT framework for yourself. Implementing and playing around with these types of agents is remarkably fun. If you want inspiration from my code base, you can find it here. Good luck, and have fun!